Zena Armstrong is a former senior Australian diplomat now dedicated to working for her regional community on the south coast of NSW. She is director of the Cobargo Folk Festival and president of the community-run non-profit Cobargo Community Bushfire Recovery Fund Inc that was established in the wake of the devastating 2019-20 bushfires. Armstrong advocates for improved humanitarian assistance to domestic disaster victims from the Australian Government. She is a former senior executive service officer in the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Her diplomatic career included working on Australia’s post-war recovery taskforce in Iraq and recovery efforts following the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami.

Yaara Bou Melhem is a Walkley award-winning journalist and documentary maker who has made films in the remotest corners of Australia and around the world. Her debut documentary feature, Unseen Skies, which interrogates the inner workings of mass surveillance, computer vision and artificial intelligence through the works of US artist Trevor Paglen was screened in competition at the 2021 Sydney Film Festival. She is currently directing a series for the ABC and is the inaugural journalist-in-residence at the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism & Ideas working on journalistic experimental film.

Cobargo Community Bushfire Recovery Fund president Zena Armstrong is dedicated to supporting the recovery of her community after the Black Summer bushfires. Recovery programs are fire-proofing infrastructure and utilities, re-planting forests, memorialising what was lost and investing in healing for their citizens.

What we’re hoping for is something that has a high level of community ownership and high level of benefit sharing for our communities.

– Zena Armstrong

The sorts of volunteer groups that I work in, we are working for the benefit of the community, for community good.

– Zena Armstrong

We are going to need volunteers to help us with this recovery. How best can we support people who are doing this work? So we decided that the money would go to community organisations rather than to individuals.

– Zena Armstrong

They were displaced people because of the loss of power. So one of the projects that we’re working on is to build a microgrid and community battery.

– Zena Armstrong

If we have another disaster or if we have to de-energise the grid at any time, the microgrid and the battery will kick in and provide power for essential services in our village.

– Zena Armstrong

What we’re hoping for is something that has a high level of community ownership and high level of benefit sharing for our communities.

– Zena Armstrong

Welcome, everyone, to 100 Climate Conversations and thank you for joining us. Today is number 40 of 100 conversations happening every Friday. The series presents 100 visionary Australians that are taking positive action to respond to the most critical issue of our time, climate change. We are recording live today in the Boiler Hall of the Powerhouse museum. Before it was home to the museum, it was the Ultimo Power Station built in 1899, it supplied coal powered electricity to Sydney’s tram system into the 1960s. In the context of this architectural artefact, we shift our focus forward to the innovations of the net zero revolution.

Before we begin and on behalf of the Powerhouse, I’d like to acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the ancestral homelands upon which we meet today, the Gadigal People of the Eora Nation. We respect their Elders past and present and recognise their continuous connection to Country.

My name is Yaara Bou Melhem, I’m a journalist and documentary film director and I often make public interest films that are at the intersection of art and science. Zena Armstrong is a former senior Australian diplomat now dedicated to working for her regional community on the South Coast of New South Wales. She is the long-standing director of the Cobargo Folk Festival and president of the community run non-profit Cobargo Community Bushfire Recovery Fund that was established in the wake of the devastating 2019/2020 bushfires. We’re so thrilled to have her join us today, please join me in welcoming Zena. Now, Zena, you grew up in England and spent your early years on dairy country in Gloucestershire. Years later, you find yourself again on dairy country in Cobargo on the Sapphire Coast of New South Wales. What drew you to the town?

The Folk Festival – I am a folk festival lover from way back and also a musician. I first discovered Cobargo as a young journalist when I was covering South Coast stories for The Canberra Times. But then when the festival started my husband and I would go, and we met a bunch of wonderful people in a very beautiful part of New South Wales. The Folk Festival has got a very strong group of people around it. It’s been running now for 27, 28 years and it’s been totally run by volunteers in all that time. It’s a group of people that have had this long involvement who are all committed to volunteerism as well as live music. A perfect mix for me, so it’s good.

And I think because we’re going to be talking a lot about community in our conversation, I suppose I want to get a sense from you about why community is important to you. What is it about community that is important to you, or establishing community?

That’s a really interesting question and one that I think is quite difficult to answer. I guess I’d say that in the sorts of volunteer groups that I work in, we are working for the benefit of the community, for community good. It’s this whole feeling that people can come together and do amazing things together as volunteers that are hard to do if you’re engaged by a company or in a business – a very different way of looking at what it is that you’re actually producing.

Perhaps by way of example, if I talk about the festival, what we do – there’s a core group of about 30 volunteers with a much larger group of another, perhaps 300 – who will come to Cobargo every year to help us produce this event. I think what we see we’re doing is creating a space and holding a space where people can actually come and walk through our gate and forget about what might be happening in real life for a few days and just enjoy that feeling of being connected, that feeling of being able to express yourself perhaps a little bit more authentically than you might otherwise, and to enjoy heaps of really good live music as well. We’re creating something that’s bigger than ourselves and there’s a heap of fun in doing it too. It’s hard work but that feeling of working together with a lot of like-minded people is something that you can’t beat.

The sorts of volunteer groups that I work in, we are working for the benefit of the community, for community good.

– Zena Armstrong

As we know, bushfires and extreme events are increasing in frequency, duration and intensity due to climate change. And Cobargo was one of the most impacted towns during the Black Summer bushfires of 2019 and 2020. In the early hours of New Year’s Eve in 2019, a firestorm moved from Wadbilliga National Park to the west of Cobargo village. We’ll talk about the wider impacts for the town, but could you first tell us what your experience was like in the lead up and during the fires?

Yeah, we had been watching these fires as they travelled down the east coast, as they came down the coast through the Currowan and then down through Batemans Bay – Durras, Batemans Bay. And we knew that at some point it was inevitable that they would hit us. I think there was a period of about two months for me, or three months perhaps, watching this progress, looking at the magnitude of these fires and just feeling there’s no way that we’re going to escape them. And on the night before the fires actually hit us, my husband and I were woken up quite early, actually, this was on the morning when the fires hit us, and we were just standing on our deck. Now, Cobargo is about 10 kilometres away from our place, but we could feel waves of heat coming at us [from] that distance, and we knew that something terrible was happening.

As we were standing there, we had every intention to stay and defend our place. We’d done everything we had been advised to do. We’ve got sprinklers on our roof. We’ve got a very extensive garden sprinkler system, sprinklers under the house, sprinklers on our water tank. We’ve got a fire pump and a lot of water on the property. And we had intended that we would stay and defend. But my neighbour across the valley called me up and said just a few words, “Zena, get out now.” And I didn’t argue with him. He’s a very laconic young farmer. And I thought, “well, if Brad’s telling me to go, I’m going”. So, we just threw a little bit of stuff in the back of our car, and we did what everybody else did and evacuated to Bermagui.

When we came back into Cobargo the next day, of course, so many people had lost their homes. Everybody in Cobargo and the district is affected in some way. We either know family, people who passed away, of course, family and friends. Friends who’ve lost homes. Everybody is affected. And we lost a third of our village [main street] in that fire. So, quite a number of the most beautiful, most historic shops and buildings that we had in our village were burnt.

And just going back to the time of the fires, did you know where to go to evacuate? Was there a designated evacuation zone for the community or were you kind of winging it?

This is a very interesting question, and I think one that we all have to face, no matter whether you live in the city or whether we’re in the country. There is no safe place. We were told to evacuate initially to Cobargo. Nobody thought Cobargo would burn. Then from Cobargo to Bermagui. Nobody thought that Bermagui would burn, but it was obviously under threat. Some people were told that they had to go from Bermagui to Narooma or to Bega, but the roads were already on fire. So, where do we go?

There are no buildings which are actually designated, fit for purpose, bushfire evacuation places. They also, ‘they’ being the authorities, asked us to go to Bega. Bega is about 30 minutes away from Cobargo through some very challenging roads. You have to go through the Brogo gorge and the Brogo gorge was in danger of catching on fire. It’s a really serious issue I think that regional areas in particular need to be looking very hard at – where does the community go?

And so, you go back to the town and what do you find in terms of what kinds of people and organisations are on the ground, responding to the disaster and assisting the community?

This disaster was so widespread that it was very difficult for governments and local council to provide the extent of the services that were so obviously needed in the immediate aftermath of the firefront going through. We had many displaced people, people who’d lost their homes, people who’d had lost significant parts of their property, people who just were so overwhelmed by what was happening to us that we wanted to gather together in one place so that we could work through this experience that had occurred. And we went to the showground. The showground is a place where we come together as a community. And it seemed quite normal – well, not normal – but it was the place where we automatically gravitated to.

The people who responded immediately were those who knew how to run the showground. It was folk festival people. That’s where we have our festival, so we know how the showground runs, and it was the Show Society people. Together we opened everything up and started to make preparations to help people. Then all the donations started flooding in. Large amounts, trucks of water and food. And that was really the only place in Cobargo where that volume of goods could be dealt with. We kept that running at the showground for six months. It was all done by volunteers and then the relief centre moved into a small cottage in the village, funded by the Community Bushfire Recovery Fund, by the unions, and a contribution also from the Minderoo Foundation.

There was a moment captured on camera of the then Prime Minister Scott Morrison, visiting the town in the aftermath of the fire and almost forcibly trying to shake the hand of a woman there. It went viral and put Cobargo on the map, for better or worse. But there’s a lot more to that handshake, isn’t there? Give us a bit of a background as to what was happening in the lead up to that moment.

It’s important to remember that this was, this still is, a really traumatised community. The former Prime Minister came to Cobargo very shortly after the fire had been through and people were trying to make sense of what had happened. Zoe, who was the young pregnant woman, she’d lost her house. She was the one who refused to shake his hand, and she was asking him about providing more funding to the RFS. We only had four fire trucks, I believe, to fight that fire in our area. We didn’t have any water. Our power had gone out by then, and the capacity to actually deal with this fire was extremely limited.

The other woman, Danielle, with the goat, she had just spent that night and much of the following day putting out embers, waking people up in their beds and telling them to get out because fire was coming through. And obviously, emotions were very heightened. The former Prime Minister, came with a lot of security into a traumatised area and there was a disconnect, I think. I think too, do Prime Ministers these days need that much security when they’re coming into a traumatised area of vulnerable people?

How do you reflect on the visit and the surrounding publicity about it?

We are going to need volunteers to help us with this recovery. How best can we support people who are doing this work? So we decided that the money would go to community organisations rather than to individuals.

– Zena Armstrong

Look, I wrote in The Guardian a piece not long after the fires where we were reflecting on Greg Mullins and the emergency managers’ call for more preparedness for what they fully understood was coming at us. This was back in April before the fires in that year. Greg Mullins made it very clear that these fires were coming and that we needed to be making preparations. And this you will recall he asked for a meeting, but the former Prime Minister wouldn’t agree to a meeting. And we do wonder if that meeting had gone ahead, would there have been much better preparation, much better anticipation if they’d listened to Greg and those very experienced emergency managers?

The challenges Cobargo faced continued beyond the fires, with much of the town’s infrastructure damaged and destroyed, as you mentioned. What were the longer term impacts of the fire?

The impacts are across several different sectors. Of course, the economic impact has been very significant, both on individuals, on farm businesses, on individual businesses in the village. On the local Cobargo economy itself. Our folk festival, for example, injects about $1.5 million into that South Coast economy. And we haven’t been able to have a festival for two years. We came back this year, albeit a little bit smaller, but that’s a significant amount of money in a small rural area like ours. But all the farm businesses that were affected, people lost their dairy herds, also shedding infrastructure all of that went. And then the loss of those key buildings, premises in our village, some 12 businesses, I think we were affected by the loss of that.

But more significantly, I think are the mental health issues and dealing with those emotional issues that are still with us even three years on. The sense now that what we had felt was a safe haven in a beautiful part of New South Wales is no longer quite as safe. And I know the people in the flood areas are feeling this too enormously, that sense that climate change is with us, and these disasters are going to come at us more frequently and with more intensity. How we actually prepare for all of that. It’s a very pressing issue for many of us living in rural Australia. I also think it’s a pressing issue for anybody living in the cities as well, particularly people on the city edge.

Now we’ve mentioned this a couple of times, the Cobargo Community Bushfire Recovery Fund, but I’d love for you to kind of talk to us about it and why you helped create it and what need you were trying to meet when it was created shortly after the fires.

The recovery fund came about because we were receiving emails – I actually received an email from the artistic director of the Illawarra Folk Festival, Dave De Santi, not long after the fires where he saw what had happened and he said, ‘How can we help?’ and that they’d like to do some fundraising for us. And if they did this fundraising for Cobargo, where would they put the money? I took [this] to the folk club – the producer of our festival – and said, a lot of people out there who know Cobargo through the folk festival want to donate very directly to help the community, what could we do?

And we decided that we would set up this fund, the Cobargo Community Bushfire Recovery Fund, which we very quickly set up as an incorporated association. [We] went out primarily in the first instance to the folk festival community, many of whom were already saying, we want to give you money, where does it go?

Because we didn’t think that we were going to raise a huge amount of money we felt that the best way to spend it was on supporting community organisations because that whole volunteerism thing was primary in our mind. We are going to need volunteers to help us with this recovery. How best can we support people who are doing this work? So we decided that the money would go to community organisations rather than to individuals. As we didn’t think we’d raise a huge amount of money, if we’d given it to individuals they might have got $200 or whatever when spread across. But $200 when you’ve lost your $750,000 home isn’t really going to help. And we really wanted to make sure that our community stays strong.

Those organisations are the community glue in a way. We have now funded 51 different projects. We’ve spent about $650,000. We’ve put another $200,000 aside for a community art project once we’ve rebuilt our main street buildings. We’ve empowered a lot of different people, and we have really helped a lot of community groups to stay together through this really difficult time.

Could you list some of those projects and how much you’ve raised for them?

Using probably around about $50,000 or $60,000 of community bushfire recovery funding, we’ve leveraged more than $23, $24 million. It’s probably more, but that’s what I know of.

And that’s through engaging consultants to help with the grant making process and engaging architects as well. And that’s for the Cobargo CBD redevelopment, the Resilience Centre –

The Cobargo Resilience Centre, which is a museum, yes.

But the biggest one, I suppose, is the Cobargo community microgrid.

Well, the biggest one is the rebuild of the main street, those buildings in the main street. And the very interesting thing about that is that we will have three quarters – well, all of that under community control. We’ve set up a community co-operative that owns [over] three quarters of that land now. The other quarter is owned by a private family who are donating it to the community. So we will have about $20 million worth of property under community management and community ownership by the time this is finished. The microgrid is currently at feasibility stage. We raised over $1,000,000 to do a feasibility and that project is progressing quite rapidly. We do have to go out and raise more funding for that. We’re looking at a five-megawatt solar farm with an equivalent battery. So, this again is going to be in the millions of dollars. And once we’ve completed the project plan, we will be going out to fundraise for that.

And what did you notice about the organisations and different government outfits that were coming into the community in order to help? What did you notice about what was working and what wasn’t?

These prolonged disasters of this intensity, whether it’s fires, whether it’s floods, are challenging us as never before. They’re challenging governments. They’re challenging our well-established charities like the Red Cross, like Anglicare. We’re seeing a lot of new foundations springing up who are trying to work in this area as well. So, the Minderoo Foundation, for example, is one and everybody is trying to work out how we are going to prepare ourselves for this future that’s coming at us.

Those organisations that have done it best are organisations, for example, like the Red Cross. I know the Red Cross got a lot of criticism in the beginning – but I think they’ve done a very good job locally, [and also] Anglicare. Both of these organisations have engaged local people and they’ve embedded them in our community. They’ve got local networks, they’ve got local knowledge, they have these trusted relationships that go back quite a long way for some, and they know in a very deep way how to engage and what the community needs.

Organisations that come in from the outside, as I’ve said, if they are coming in with preconceived notions about what’s needed, are going to find it more difficult and perhaps will be less successful. Often the success comes down to an individual who has done a remarkable job above and beyond, rather than the organisation. I did some work in a past life on reconstruction in Iraq as a member of the Foreign Affairs Iraq Task Force. And we were working on reconstruction in a post-conflict situation. I think if I was to do that job now, I would do it very differently. I went in as a government officer with preconceived ideas about what a recovery would look like, what people needed in a recovery. I had no idea. We sometimes say to ourselves in our groups, ‘ah another, I’m from the government and I’m here to help approach.’ And the irony in that is very pertinent to me when I look back on my past life. Living through a disaster and then working to help community recovery brings a very different perspective.

They were displaced people because of the loss of power. So one of the projects that we’re working on is to build a microgrid and community battery.

– Zena Armstrong

So, it seems to me that community led funding, community led distribution models for funding appear to be the way to go, in your opinion. Is that sustainable and ongoing?

It became very obvious to us that we needed to find funding to rebuild those parts of the village that were burnt. We also had this experience where – and this relates very directly to the climate change issue – the power went out in our village and was out for more than ten days because the power poles were burnt. With the loss of power, we lost water so we couldn’t fight the fires. We lost the capacity to pump our sewage because all the sewage is on electric pumps. The doctors were working by torchlight. We had no refrigeration and many people had to evacuate for that reason – not because of the fires – but because we had no power. They were displaced people because of the loss of power. So one of the projects that we’re working on is to build a micro-grid and community battery using a solar farm.

Now, in order to do these projects, we need to go out and get funding. And the community led grant recovery programs were our opportunity. In order to put together a suitable application, when you are competing for this funding against other government departments, other businesses –big corporate businesses – and your local councils, you actually need to have the resources to do that. In Cobargo, we were able to buy in those resources because we had the fund. We brought in an organisation called Australian Business Volunteers and they provided us with expert advice about business cases, about building narratives, and putting together grant applications. And we were also able to pay for architects to help us develop architectural concepts for the rebuild of the main streets and the disaster refuge.

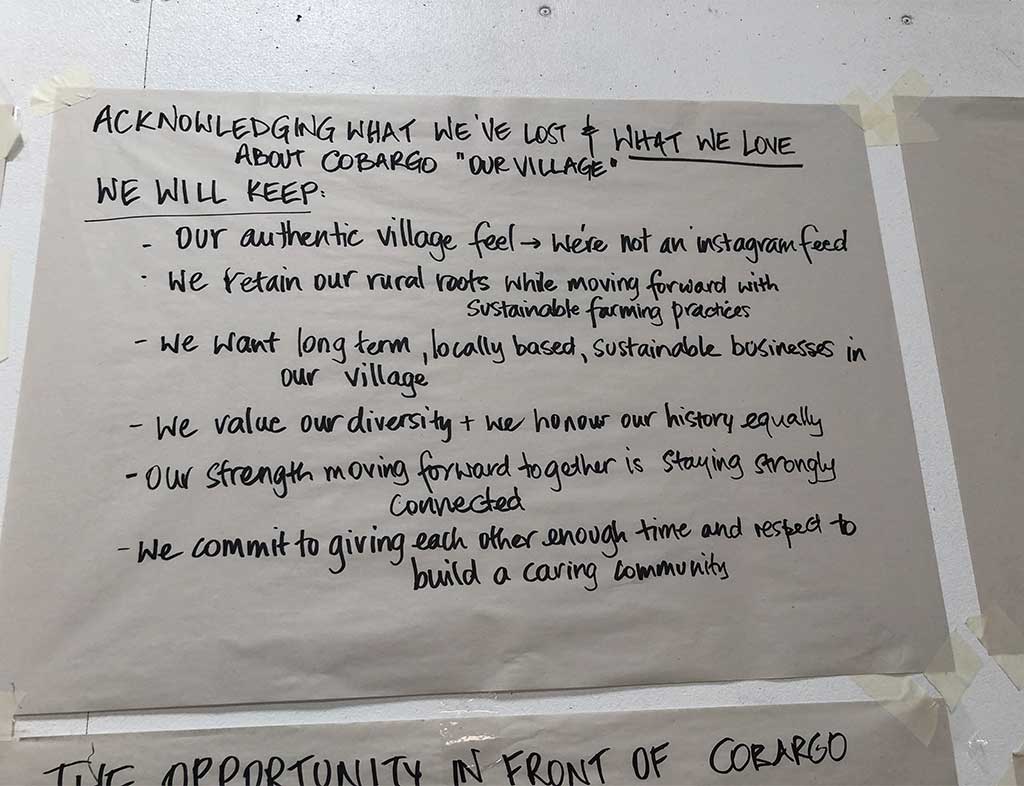

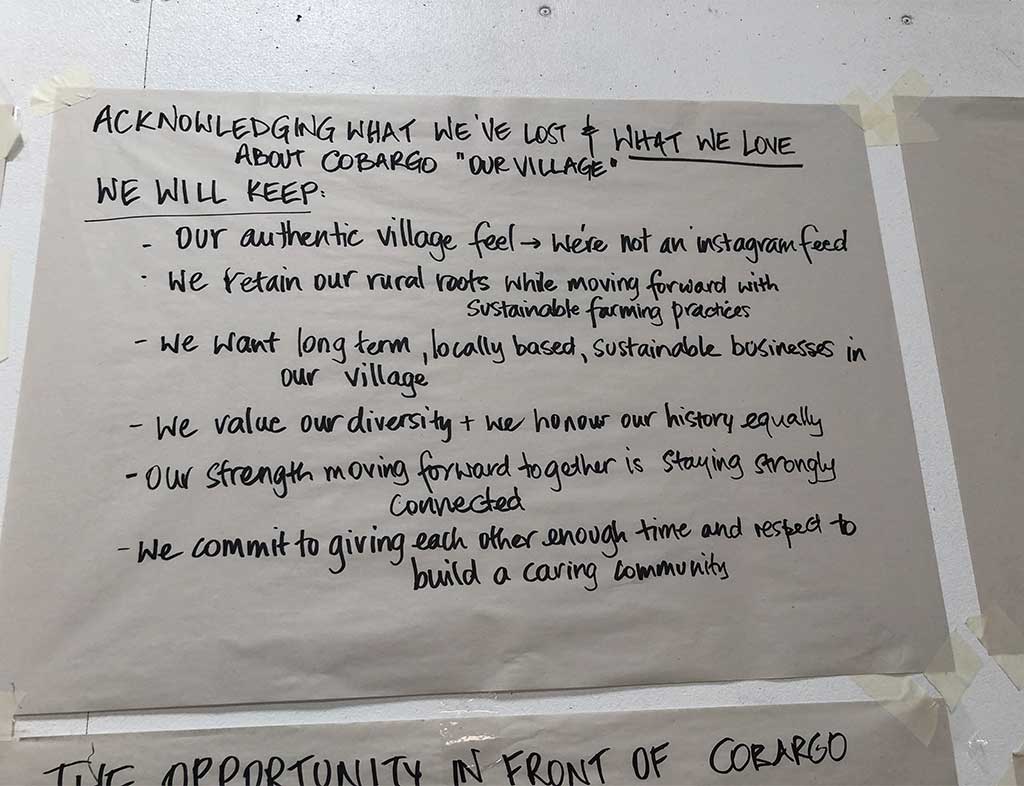

We were only able to do this because we had this money in the fund. Some of that funding was leveraged by these groups to develop their grant applications – so that they were fully competitive – and then submit them. Communities that don’t have that capacity had to rely totally on whatever volunteer experience was available to them. Communities have different amounts of capacity and capability. Some very small communities were not able to submit because they just didn’t have that capacity available to them. They didn’t have the resources. So, if this is the way that government is choosing to continue to help communities recover, then they need to actually provide the resources to help those communities to develop strategies, projects and plans. We also undertook a very extensive community consultation, which again was because we had the people with the experience in community consultation already in our village. They ran a consultation that was based on a deliberative process – a little bit different from how council might have chosen to run it. That drew together as many people as we were able in the very beginning to talk about what the priorities were for the rebuild and recovery.

Tell us what a microgrid is and what form you would like it to take in Cobargo and what other examples you’ve seen of a working microgrid in other communities.

We’re looking at, as I said, a five-megawatt solar farm, which will be on the edge of Cobargo Village with a battery. We’ve got two aims for this. The primary aim is to provide energy resilience. If we have another disaster or if we have to de-energise the grid at any time, the microgrid and the battery will kick in and provide power for essential services in our village. Depending on the size, we may also be able to provide essential power for a number of the houses in the village as well. It’s being developed with a company called ITP Renewables and we are close to identifying a location for it and hopefully to take the next steps. The innovative part of this is the islandable nature of it – if the power grid goes down or has to be de-energised, for example, because of high winds. Quite a number of fires in our area are started by powerline clashing and sending a bolt of energy down into the ground and starting a grass fire. We had one of those in September 2019 before the big fire came through, which was a bit of a harbinger of things to come. We are looking at ways in which we might be able to protect our village in extreme weather.

What we’re hoping for is something that has a high level of community ownership and high level of benefit sharing for our communities. We’ve targeted [this] in all of our discussions that we’ve been having with the developer, with the engineering team, with Esssential Energy, the Australian Energy Regulator and the market operator. We’re emphasising that we really want to see community benefits maximised, which hopefully may be realised in terms of lower power costs and stable energy costs for people living in our district. Often it’s not the fact that the energy prices are high but the price fluctuations – once they go up, they stay up. That’s what people are finding very difficult at the moment – they don’t know what their power bill looks like from month to month.

And talk to us about what sort of policy frameworks are in place and whether the right infrastructure is in place at the moment to support this microgrid.

The infrastructure issue is a serious one for regional areas like ours. We’ve yet to discover with the microgrid what challenges lie there, but we’re also trying to create four community hubs that can act as cool refuges during extreme heat by putting in independent solar and batteries there. What we’re finding is that the connection into the existing power infrastructure in our village is quite difficult. The infrastructure is very old. We’re also looking to put in EV charging stations as well. The actual infrastructure in place in the village will need upgrading and that’s a cost. I think many small villages, regional areas across Australia are going to find this as they start moving into the energy transition. “Electrify [everything]” is going to come with considerable challenges because of our ageing power infrastructure.

How is the community doing now? What stage of recovery are you up to?

Well, we’re three years on, we’re coming up to [the]

three-year anniversary. I think it’s still really tough.

Many people are still living in caravans. I was visiting

a friend of mine – he’s got his house to lockup stage,

but he’s still in his van because he can’t get a

plumber. He can’t get an electrician because of the

shortage of tradies down in our area. Other people have

had to wait – delays with the DA processes, for example,

and all through this, prices are increasing, of course,

the prices for materials. There are many more

regulations that have been brought in that people have

to observe. Because they’ve been through a bushfire and

they’re flame affected, their bushfire ratings on their

building have increased, so that increases the costs.

You need to do more to strengthen your building. These

people are facing, some of them probably going to face

another winter still in a caravan. There are people I

know – you can see them on the roads – who are living in

their cars. There is not enough accommodation, not

enough rental accommodation. There’s a shortage of

social housing.

How are we going? We are dealing with a lot of different

issues. But there’s hope. We’ve got funding. We’re going

to go ahead and rebuild, yeah. And I think we’re looking

forward to a brighter future together. But yes, it’s

tough.

If we have another disaster or if we have to de-energise the grid at any time, the microgrid and the battery will kick in and provide power for essential services in our village.

– Zena Armstrong

A lot of the times when we talk about building resilience for communities or adapting to climate change, we’re thinking about perhaps throwing more resources at authorities or police forces or the RFS. But what about the arts and culture organisations as well that form the fabric of communities? How can we build more resilient communities through arts and cultural organisations?

There’s a lot of work going into working out how to catalyse resilience in communities at the moment. This word ‘resilience’ is one that we struggle with at the community level. For us, I think what we’re talking about is really adaptation. How do we prepare communities to adapt to climate change? The formal definition of resilience includes the capacity to bounce back. But if you’re already been through one disaster, for example, as we have or as they have in the floods and [are now] facing prolonged and successive disasters, what does resilience mean in that sense? And how do we actually try and generate resilience in our communities and ourselves, in our communities? For us, it comes back to social capital.

We have a lot of social capital in Cobargo and we had a lot of social capital before this through organisations like the CWA, the Show Society, the RFS, the folk club. And [through] those communities, those organisations, we all know each other. We are a small village, so there’s lots of trusted relationships between various different groups and we have used those trusted relationships to actually mount this recovery. But not everybody and not every community has that. So, how do you actually help communities to build that, to develop that? I think one of the ways, as you’ve just said, is through art and culture and events, creating opportunities where people can come together in safe spaces to engage with each other, to build that trust, and also to be able to take that time out where we can just have fun together at the Show, for example, or at the Folk Festival.

There is a strong message for governments in this. When you have a recovery or a resilience effort that is being managed by the emergency responders or by the police, you are going to inevitably be working in a framework where they are thinking about command and control, where they’re thinking about evacuation, where communities, where individuals, where people are actually a liability that have to be cleared out of an area so that the emergency services or the first responders can do their job, rather than seeing that community and those people as assets that you might be able to draw into your response. Not everybody of course, you probably need to be ensuring that the vulnerable parts of your community are well looked after and in safe places – but there are a lot of people in communities who really want to help.

We saw it in the fires with people like Danielle and her husband dealing with the embers. We saw it in Lismore where the people took their boats out – this is going to happen. So you can either as an emergency responder or as police, work with this and build it into your strategy, or you can see it as a hindrance and then it becomes much more difficult. I think emergency responders and the police, they often don’t understand. They perhaps don’t see the value in funding and supporting arts and culture. For them, I think it probably just seems so distant from an emergency response. How can that [funding] be helpful? But it is, because what it does is build social capital. That social capital may be used in an emergency response – but it’s particularly useful in relief and recovery.

If we didn’t have that level of social capital in our village, where people stepped up and opened the relief centre, got it running, managed the logistics of all of these semi-trailers that were coming in, dealt with traumatised people with tremendous empathy because they were our friends and neighbours and our family, friends and neighbours. We knew them, we felt with them. You can tell that I didn’t lose my house because I’m kind of, I’m not putting myself in the position of somebody who required that support. I was one who was trying to give that support. That quality of response is not one that’s going to come easily from government or from council. But there is a place for government and council response. We just need to work out how do we do it together. How do the authorities, government authorities, council, empower local communities to take agency in this case and how do they legitimise it? I think what we’re asking for is, we want agency, and we want to be acknowledged as legitimate actors in this space.

Everyone, please join me in a round of applause for Zena. To follow the program online, you can subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. You can also visit the 100 Climate Conversations exhibition or join us for a live recording like this one. You can go to 100climateconversations.com and just search for 100 Climate Conversations in your pod catcher of choice.

This is a significant new project for the museum and the records of these conversations will form a new climate change archive preserved for future generations in the Powerhouse collection of over 500,000 objects that tell the stories of our time. It is particularly important to First Nations peoples to preserve conversations like this, building on the oral histories and traditions of passing down our knowledges, sciences and innovations which we know allowed our Countries to thrive for tens of thousands of years.