Climate scientist Dr Sophie Lewis was appointed the Australian Capital Territory’s Commissioner for Sustainability and the Environment in 2020. Prior to that she was an academic with a research focus on how climate change contributes to weather extremes, such as the incidence and severity of fires, floods and droughts. Lewis was named 2019 ACT Scientist of the Year in recognition of this work. She has contributed as a lead author on several Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports which are used to set international carbon policy targets, such as the United Nations’ Paris Agreement.

Rae Johnston is a multi-award-winning STEM journalist, Wiradjuri woman, mother and broadcaster. The first science and technology editor for NITV at SBS, she was previously the first female editor of Gizmodo Australia, and the first Indigenous editor of Junkee. She is a part of the prestigious ‘brains trust’ the Leonardos group for The Science Gallery Melbourne, a mentor with The Working Lunch program supporting entry-level women in STEM and an ambassador for both St Vincent De Paul and the Australian STEM Video Game Challenge.

Former climate scientist Sophie Lewis is the ACT Commissioner for Sustainability and the Environment, determined to support positive outcomes for the territory in the face of climate change. An independent voice that examines public complaints and undertakes environmental investigations, the Commissioner is a unique statutory role that bridges government and community engagement.

I do think there is so much potential for us to halt that trajectory that we’re on to a future I don’t want my children to live in.

– Sophie Lewis

The work that we’ve been doing in my office is around … trying to account for our scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions and looking at how we can reduce the overall impact of Canberrans and our lifestyles on the environment.

– Sophie Lewis

For the ACT, actually 94 per cent of the total emissions are scope 3.

– Sophie Lewis

Instead of just focusing on our scope 1 emissions, which can be really hard to abate … we can make some quick gains with scope 3.

– Sophie Lewis

We’re really looking at both understanding [scope 3] emissions in more detail, but also trying to tackle some of them and reduce [them] and not just wait for other jurisdictions because that’s not something the ACT has done.

– Sophie Lewis

We would really like [Western environmental reporting] to sit alongside cultural indicators that are provided and determined by Ngunnawal people, that we have both of those sitting within a State of the Environment report.

– Sophie Lewis

I do think there is so much potential for us to halt that trajectory that we’re on to a future I don’t want my children to live in.

– Sophie Lewis

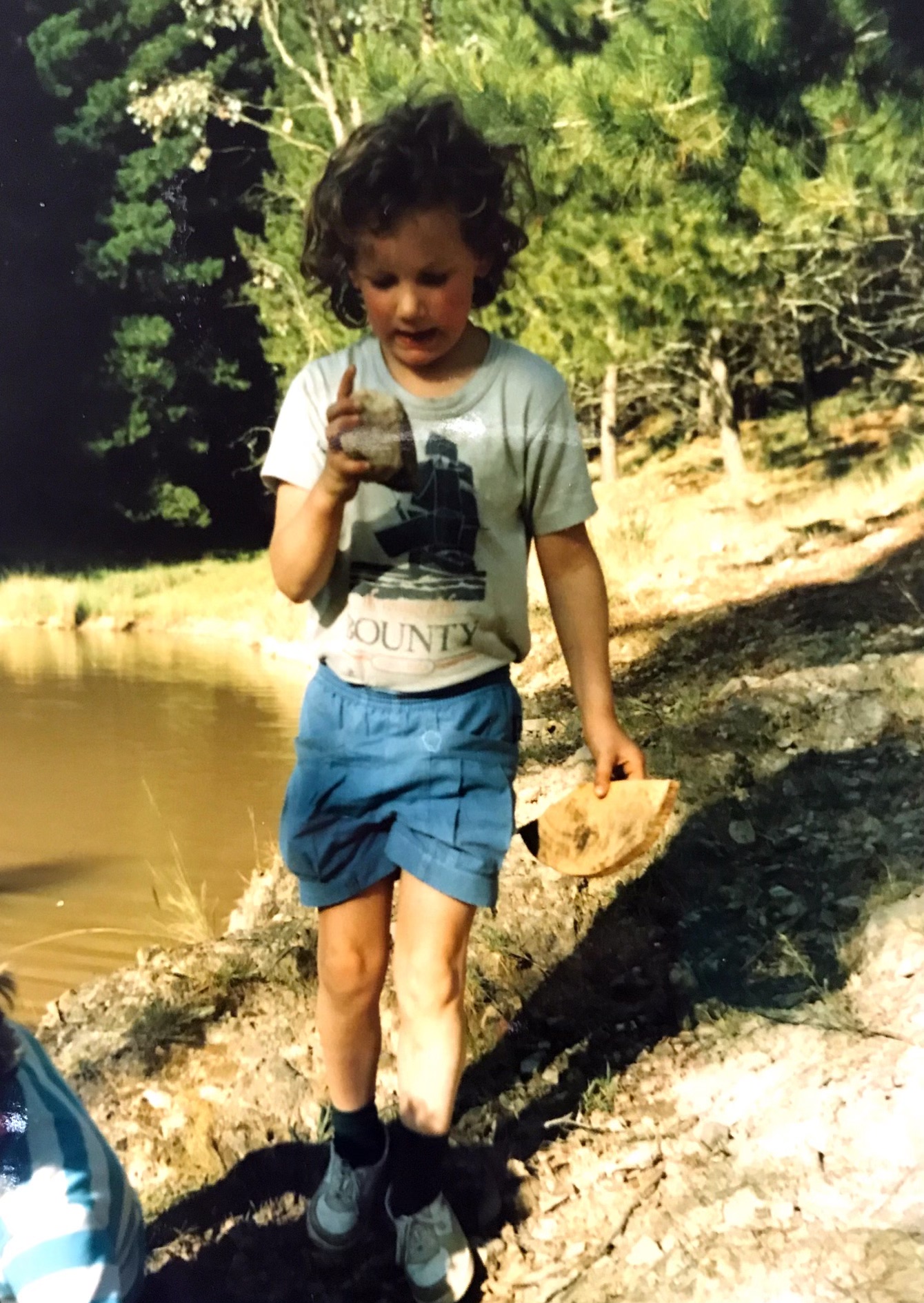

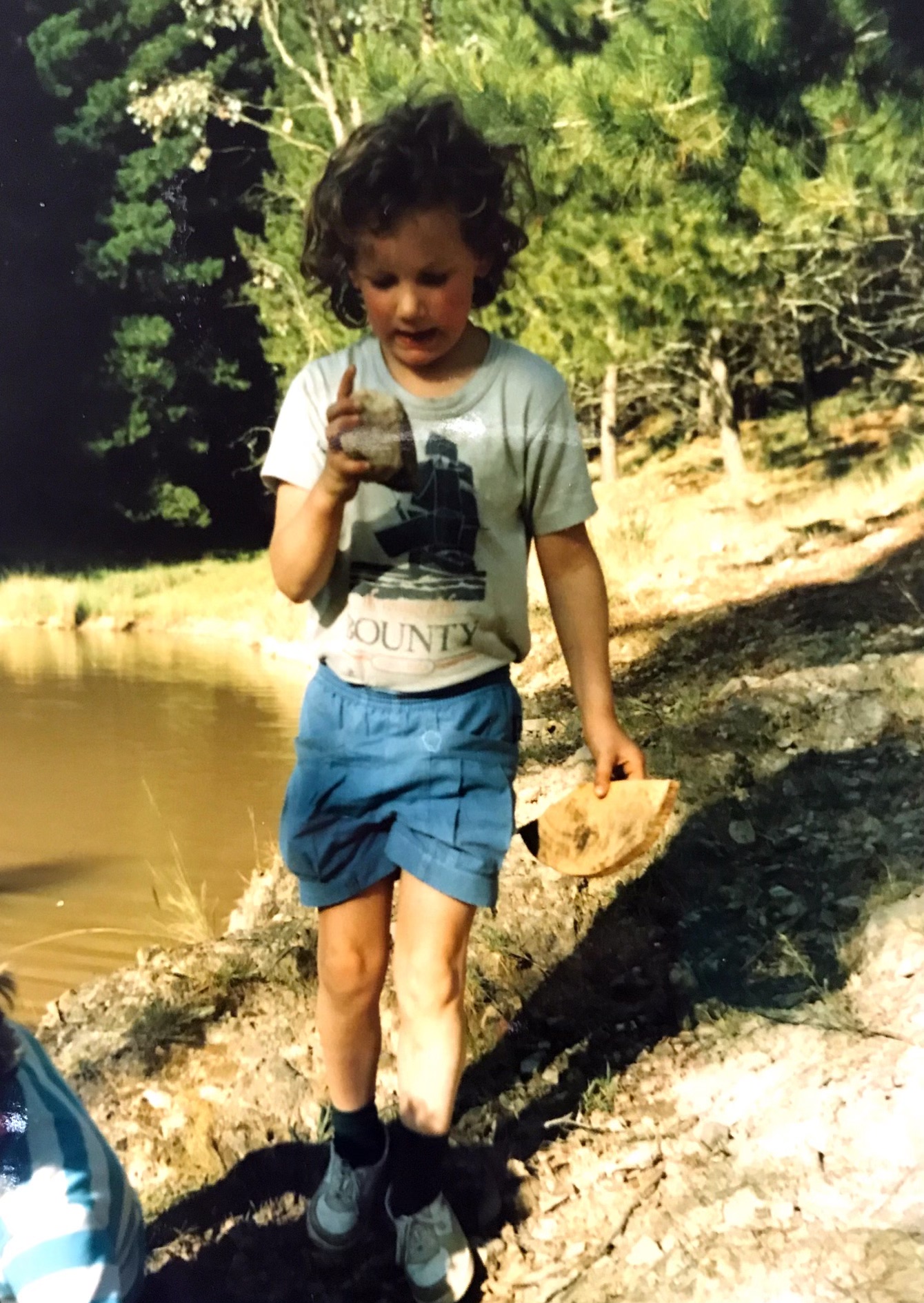

Welcome, everyone, to 100 Climate Conversations. Thank you so much for joining us. Yiradhumarang mudyi Rae Johnston youwin nahdee, Wiradjuri yinhaa baladoo. Hello friends. My name is Rae Johnston. I’m a Wiradjiri woman. I was born and raised and currently live on Dharug and Gundungurra country. That’s where I have responsibilities to community and country. And it is an absolute honour and privilege to be here with you today on the Unceded land of the sovereign Gadigal. And I wish to pay my deepest respects to their Elders, past and present, and also extend that respect to any of my First Nations aunties and uncles, sisters and brothers that are here with us today for this conversation. Now, as we begin today’s conversation, it is important to remember and acknowledge and respect that the world’s first scientists and technologists and engineers are the First Nations peoples of this very continent from the world’s oldest continuing cultures. Despite all attempts to erase them. Today is number 59 of 100 climate conversations happening every single Friday. And this series presents 100 visionary Australians that are taking positive action to respond to the most critical issue of our time, which is climate change. And we are recording live today in the Boiler Hall of the Powerhouse museum. Before it was home to the museum, it was the Ultimo Power station. It was built in 1899 and it supplied coal powered electricity to Sydney’s tram system right up until the 1960s. And in the context of this architectural artefact, we are now shifting our focus forward to the innovations of the net zero revolution. Now, in my everyday work, I’m a STEM journalist and a broadcaster and I have the opportunity to speak to people using science and technology to help the planet. And today I am sitting beside one of those people. I have Sophie Lewis, who I am looking forward to chatting with today. Climate scientist, Sophie Lewis was appointed the Australian Capital Territory’s Commissioner for Sustainability and the Environment in 2020. Prior to that, she was an academic with a research focus on how climate change contributes to weather extremes. She was named the 2019 ACT Scientist of the Year in recognition of this work and has contributed as a lead author on several intergovernmental panels on climate change. And we are so thrilled to have her joining us today. Please join me in welcoming Sophie. Now I want to talk about your background and your connection to climate. So, you knew that you wanted to be a scientist from the age of four, I believe. What inspired that curiosity and that love of the natural world?

Yes, I have had this kind of deep love of the environment and our natural world since I was a very young child. And I was very lucky as a child that we spent a lot of time outside. My parents took us out camping, out hiking, were always outside collecting things. And a really big event for me was when I was around four years old my parents took me out stargazing and were supposed to be looking for Halley’s Comet. Which is this comet that does a very infrequent pass by Earth. And that night we didn’t see anything. But something about that was really critically important for me. It was a really transformative experience as a child, and although I wouldn’t have articulated at four that, I wanted to be a scientist. It was a passion through all of my childhood. You know, any time I had the opportunity at school to make a school project or assignment about something to do with science, I always did that. So, that was a consistent dream throughout my childhood and a consistent interest, and I took that into high school and then into university.

How wonderful to know from that age what it was that interested you the most and to be able to follow that through. Has it been a rewarding experience?

It was absolutely has been rewarding. And it was wonderful that I’ve always had this kind of way of connecting and trying to understand the world through that scientific lens. But throughout university or throughout my early career, I definitely took detours. It was quite a kind of circuitous, meandering, changing what I was interested in. And I’m not a very strategic thinker. So, saying that I’ve wanted to be a scientist since I was four, and then you’re reading my bio and talking about being the ACT Scientist of the Year a few years back makes it sound like I just set my mind to it and I was highly ambitious, so I just want to dispel that. That was not the case at all.

So, what I’m hearing from you is that it’s okay to have a non-linear path doing what you’re achieving. And that’s kind of how science works as well, isn’t it? You know, sometimes you set out to have a certain objective and that’s not how it turns out. And you don’t get to places the way that you expect.

Yes, that’s a really good parallel with kind of my career and the kind of mechanics of doing science. And that’s something I think kind of undertaking that scientific training really taught me is kind of the value in making mistakes. And when I was doing my Ph.D., when I was doing my honours research, I think probably looking back, the more catastrophic the mistake, probably the more important it was to the project or to my learning. And, you know, things like realising I was actually kind of appalling at lab work. I just don’t have any attention to detail. I’d lose samples, I’d make these interpretations that were wildly inaccurate and learning from that and then seeing kind of where I was better placed to make a contribution to science.

Where were you making those contributions as a climate scientist? What were you focusing on?

Yes, so after I finished my Ph.D, I was looking at this link between climate change and extreme weather and climate events. And at the time that I was doing that work, it was I think, a really hugely important research field. It was just starting up that were starting to be able to kind of scientifically draw those links. But it was also at a time when those issues were highly politicised. So, after any kind of extreme weather or climate event and we’ve had so many of these hugely catastrophic events over the decades, you know, thinking back to the Queensland floods or extreme bushfire events. Typically, after every single one of those events, people are asking or thinking, why did this happen? Is it climate change? And in one sense that’s a really natural question. Like we want to know why did this happen. Will it happen again? And those questions can be really useful because we know that if a say a flood was made worse by climate change, having that understanding is really going to help in terms of adapting and protecting our community from those types of events in the future. But also, when me and a wider group were really digging into that research field, that new research field, that was at a time when those events were becoming politicised. So, that question was being asked for really highly political reasons and really often in the spirit of denial of the fundamental science of climate change. And to me that was really detrimental because if we back in 2011, 2013 are saying, well, this has nothing to do with climate change, this was just really bad luck, this was a natural disaster, Let’s just rebuild and move on. Then we’re really locking in those events happening time and time and time again.

How does it feel working on extreme weather in particular at that time when Australia was notoriously lagging behind in addressing climate change and in that state of denial as well?

Yes, it was tremendously difficult, and I think that took a really huge toll on me. You know, I’ve described that I’m pretty reactive, but I’m also quite an emotional person. And I wasn’t someone who really took a lot of value from the technical aspects of the science. So, some of my colleagues were really fascinated and excited and energised by the technicalities of the science. But for me, my enjoyment of that work was really through feeling like it was very important. It was important work to be providing for policymakers, for community members. There was a whole series of events that occurred during that period of my career that meant that I’m no longer working in that field, and I think probably the one that was really hugely impactful in that decision making to leave was the Black Summer bushfires. That summer had occurred after we had had increasing record breaking, increasing extreme temperatures, drought. And again, that background of denial from particularly at the federal government level that there’s nothing to say here. We don’t really have to worry. No one should be particularly concerned. And during that time, I was living in Canberra, and we were particularly severely affected by the bushfires. So, we had weeks and weeks and weeks of that horrific smoke, day after day of having the worst air quality in the world. Every night when the wind would change in Canberra and the air would blow up from the coast smoke would fill our home. Your home is this safe place. It’s this place of security. It’s where I put my daughter to bed in her cot and knowing that some of our friends were out there as volunteers, trying to protect our environment, protect our homes, protect our communities. And at the same time, we’re hearing these messages that, you know, we’ve had fires and we always will have fires and there’s nothing we can do. That infamous I don’t hold a hose. And at that time, it felt like this absolute deep betrayal. And I began to wonder, for me personally, not that I’m devaluing the science I think we have so much to do to understand what impacts are going to occur in terms of climate change and information about the climate system. But for me, I began to really realise my contribution to these issues wasn’t going to be through writing those journal articles.

Absolutely. So, the ACT in particular, you’re talk about living in Canberra there, it’s achieved a lot in the renewable space and taking positive action on climate change. What would you say is some of the more outstanding commitments made by government and community in that area?

Yes, so I think that’s one of the reasons why the job that I’m in at the moment is so enjoyable to me is, there’s always more to do. But the ACT is a jurisdiction where we do have these kind of really ambitious progressive policies, particularly around climate change and climate change mitigation. And one of the big ones is back in 2020, we had 100 per cent of our electricity coming into the ACT was from renewable sources, which was one of the first jurisdictions to do that and really kind of led the charge there. But there’s a lot more that’s occurring in that space, in the ACT things around like electrifying homes, getting out of gas, electrifying a whole bunch of vehicles. You know, some of the work that we’ve been doing in my office is around things like trying to account for our scope three greenhouse gas emissions and looking at how we can kind of reduce the overall impact of Canberrans and our lifestyles on the environment, and not just in terms of the typical greenhouse gas accounting.

In May 2020, you were appointed the ACT Commissioner for Sustainability and the Environment. Can you tell us about that role? What does it entail?

Yes, I say I have the best job in Canberra. It’s a really great role. So, part of that is because it’s quite a varied role and it’s relatively unique. So, not that many jurisdictions have this commissioner role, and the role of the commissioner is we have several, I have several functions. One of them is around community engagement, which is fantastic. I get to spend a lot of time talking to community members, talking to school kids, finding out what people are concerned about or their thoughts about the environment. I undertake investigations into environmental issues and one of the really big ones and really important ones is the State of the Environment report. So, every four years my office, which is independent from government. Undertakes this comprehensive evaluation of the environment of the ACT and then that information into the public domain. And to me, that sounds basic. That should be someone’s job, that on a set schedule, we should take stock and evaluate the health of our environment. And then that data, that information and assessment should be public. But that doesn’t occur in all jurisdictions. So, we know in Tasmania, I think we’re up to 13 years overdue for a State of the Environment report. And we also note at the federal level, the last State of the Environment report was significantly delight in terms of its release into the public domain. So, I think it was due around December 2021 and it didn’t come out until after the federal election, which occurred in May the following year. And that State of the Environment report, it was sobering. I don’t think it was necessarily surprising to those working in that space, but the data and assessments in that report showed some really significant issues with how we’re managing the environment federally and the state of the environment.

What kind of issues.

And so that was really around things like climate change, but mainly around biodiversity loss and this biodiversity crisis. So, that’s information that is fundamental to understanding our environment and that’s information that should be released into the public domain. So, to me, that’s why it’s so important to have a role like mine where someone is charged with that responsibility.

So, that investigation that you published in 2021 was at the request of Minister Shane Rattenbury on the scope three emissions in the ACT. Can you talk us through the different emission scopes? What does this mean?

The work that we’ve been doing in my office is around … trying to account for our scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions and looking at how we can reduce the overall impact of Canberrans and our lifestyles on the environment.

– Sophie Lewis

Yes, I absolutely can. And when we were first looking into this investigation, we realised that this was going to be the huge problem is as soon as you say scope three everyone has already left the conversation because it’s not that enticing. It doesn’t sound that exciting.

Needs a marketing team.

Yes, it really does. It really does. So, greenhouse gas emissions are broken up into different categories, so scope one and scope two emissions refer to what occurs within a jurisdiction. So, if we draw a boundary on a location like the ACT or Australia, scope one and scope two emissions, all the greenhouse gas emissions that occur from activities within that boundary. So, for the ACT, let’s just imagine going about an everyday activity. So, I’ve got to drive to pick my kids up from school and then I’m taking them to the shops and then we’ll come home. So, getting in the car and driving, that’s our scope one emissions because that’s occurring inside the ACT. And then when we’re at the shops, they have the lights on at Woollies. That’s scope two emissions. That’s what’s coming through in the electricity grid.

So, it’s coming from out of the area but –

And in the ACT we have zero scope to emissions because as I said, we’ve cut out – we’ve got our renewables. So, the ACT we’ve really only got scope one and scope three. In traditional greenhouse gas accounting, so when a jurisdiction, say New South Wales or Australia or the EU say they’re going to hit net zero by whatever date, say 2050, what they’re talking about is their scope one and scope two emissions are going to be net zero. And that’s just the way this accounting occurs. There’s nothing dodgy there, that’s just the way the accounts work. And that’s how all the jurisdictions do it. And that’s how the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change states that we account for these emissions. But when we think about my – picking up my kids and then going to Woollies, I think most of us already have a sense that that actually doesn’t cover the full carbon footprint of that activity because I had to have my car.

Exactly.

For the ACT, actually 94 per cent of the total emissions are scope 3.

– Sophie Lewis

So, there’s a greenhouse gas footprint in my car that was made in a factory wherever that was. Could be China could be Japan could be anywhere that came over on a ship. Then what about when I pick up whatever for dinner roast chicken. That chicken has been farmed somewhere, probably not in that ACT. And that had to come in. And we know that there’s greenhouse gas emissions associated with agricultural activities. So, when we look at it, an activity, whatever simple activity, the clothes that I wore to go to the shops, the soccer ball that my kids were using at school, there is a huge quantity of emissions, greenhouse gas emissions that occur in all of those activities. So, my beautiful lifestyle with my kids in Canberra actually has a huge carbon footprint that isn’t covered in scope one emissions. I think most of us have a sense of this because we know some of the basic information around these kind of personal carbon footprints. If you ask most people, is eating red meat good for your carbon footprint? Most people would be like, no, but it’s delicious so I do it anyway. So, I think we have a sense that the standard, you know, we’re going to hit net zero by 2045 doesn’t cover everything to do with what occurs economically. And in this report, we’re asked to look at well what are the scope three greenhouse gas emissions for the ACT. And this was a really important question because no other jurisdiction has done this before. And what we found was the ACT actually 94 per cent of the total emissions are scope three.

And of those scope three emissions, which ones are the biggest contributors and the toughest to tackle?

Oh the toughest to tackle is yes, probably a lot of them. So, we know in the ACT we don’t produce much. We’re not a manufacturing state, you know, we don’t have a big agriculture sector.

A lot of talking.

A lot of talking. Yes, it’s goods and services coming into the ACT. So, some of the big ones we focused on our report to try and understand these emissions were around food and also around the construction sector. And that’s where we tried to highlight where we could be making cuts. We did have some people asking us, well, why would we look into this? Because if we’re talking about carbon footprint coming in from other jurisdictions, that’s someone else’s scope one. So couldn’t they deal with that? You know, if we’re importing our cars from wherever it might be overseas, that would be Japan’s scope one emission. So, let them sort it out. But what we saw in this report was that there were likely to be places that we could target and intervene to cut those 94 per cent of emissions in a way that would actually be quite quick and quite effective. Instead of just tackling some of that really hard to do scope one emissions.

So, there’s a lot of factors that need to be considered when you’re understanding scope three emissions, it sounds like. How do you actually measure them though? Because it feels like they’re coming from everywhere.

Yes, absolutely. And that’s why we can’t measure them in a way like we measure temperature. I go in there with my thermometer, right? You know, back in my uni days you directly measure the temperature. So, we don’t measure them. We use models. So, we essentially use economic models that are tied to carbon. And, you know, we get a whole lot of ABS data and a whole and financial data. And when I say we, I mean we got an expert consultant from UNSW.

Fantastic.

To help us with this and we use these models that really look at kind of the flow of money because we know that where a financial transaction occurs that has a carbon footprint associated with it.

What were some of the key recommendations that you made in that report?

Instead of just focusing on our scope 1 emissions, which can be really hard to abate … we can make some quick gains with scope 3.

– Sophie Lewis

Yes, so we made recommendations that we’re really looking at both understanding these emissions in more detail, but also trying to tackle some of them and reduce our scope three greenhouse gas emissions and not just wait for other jurisdictions because that’s not something the ACT has done. We tackled our scope two emissions very effectively. We didn’t wait for others to do that. So really, as I said, this whole investigation was really innovative because other jurisdictions hadn’t done that. So, what we suggested was we start to really settle on a method for measuring these and reporting on them and then looking at the ACT government trying to reduce their carbon footprint. So, quite a few of the recommendations were around that. We also looked at things like food and organic waste. We know that food and organic waste goes into landfill that releases methane and other greenhouse gases. So. Trying to increase awareness of that and reduce the flow of compostable material into landfill. And then we also made recommendations around building construction. So, I said that instead of just focusing on our scope one emissions, which can be really hard to abate, it can be really hard to reduce those to meet that net zero target. We can make some quick gains with scope three, and that’s where we saw that in terms of buildings, there’s some really fantastic new products emerging that are low carbon. There’s different things we can do with our building design. We can often make homes smaller without losing kind of their liveability. There’s lots that we can do there that would significantly reduce that scope three footprint.

How did the government receive those recommendations? Has anything been implemented?

Slowly. Not many of them were agreed to by government, which means when a recommendation is made by my office and it’s agreed to, that means that it’s accepted and fully funded. But we do get agreement in principle to several key recommendations, which is also really exciting because that means that they’re slowly starting to be implemented into policy and programs and we’re starting to see more discussion about scope three emissions in procurement in major projects. So slowly, but still very exciting that we’re still talking in this space.

How do you keep momentum when you know that only some of the recommendations are going to be acted on or they might be a hold on some of them for a period of time?

It can be disappointing when we don’t have recommendations accepted, but we don’t write all of them anticipating that. So, we like to write fairly ambitious kind of stretch recommendations and we don’t expect they’ll all be taken up. I think really what we’re looking at with these reports often is just adding an issue to the agenda and whether that’s something like reduction in single use plastics or scope three greenhouse gas emissions. The fact that we’ve been directed to undertake this report and we’ve had the opportunity and the resources to look into it and then to present that I think is hugely important for adding that to kind of the environmental agenda for the ACT. So, we try not to focus too much on how many recommendations are accepted and how they’re progressing, although that is important and we do track that, we try to look more about, you know, has this actually generated kind of substantial conversation and is there momentum? Is that still occurring, you know, several years after an investigation has been tabled and published?

Can you tell me about any other investigations that are being undertaken at the moment? What are you working on.

At the moment we’re really ramping up for our State of the Environment report, so that’s due to be tabled in December of this year and that is really a huge body of work because we’re looking at so many aspects of the environment and that requires so much kind of interaction with government, with various groups, with community to get the data, to understand it and to make assessments, and also things like trying to understand more about things like Ngunnawal understandings of the health of our environment and incorporate that into the report. So, they really do take a considerable period of time.

So, when you are working with Ngunnawal people, with Traditional Owners in those areas, are you seeing even at this early stage how that traditional knowledge could shape your work going forward?

We’re really looking at both understanding [scope 3] emissions in more detail, but also trying to tackle some of them and reduce [them] and not just wait for other jurisdictions because that’s not something the ACT has done.

– Sophie Lewis

Yes, absolutely. So, traditional environmental reporting is very much focussed on kind of metrics and indicators to determine the health of the environment, and we would really like that to sit alongside cultural indicators that are provided and determined by Ngunnawal people. That we have both of those sitting within the State of the Environment report. And that’s what we started to see with that federal report that was published just last year was that there was this kind of huge leap in recognition of the understanding that Indigenous people in various countries could provide in terms of understanding the health of their country.

It’s heartening to see that being implemented, though, because it’s difficult to know whether or not people are just going to be calling for it and then it will be ignored. So it’s heartening.

It is. And yes, that’s to be seen, you know, whether actually those assessments and those understandings of the health of country will actually be used in things like management practices. But I’m very hopeful, too.

So in 2017, you wrote a piece that’s called I’m Worried Having a Baby will Make Climate Change Worse. And that was exploring that tension between wanting a family but being worried about the potential impacts on the climate, which I think is something that a lot of people can relate to. As you mentioned earlier, you do have two beautiful children now. What is your message to those who are also grappling with those same considerations?

I love that you think that I’m going to have a message and I kind of hate the title of that, that was given to that piece. It’s also very apt –

Really? Not your title? That was the editor? Blame the editor –

No but it is very apt because, when it took a very long time for my partner and I to have our children, we had quite a struggle with fertility, and we did spend a lot of time kind of thinking about how we would be as parents and what we would be as a family and why we wanted children. And it was something we wanted. So, it wasn’t a decision as such. Like we didn’t make a decision, we want children. We just knew we wanted children. And that was going to be very important to us. But at the same time as that, I had this deep awareness of the impact of our lives in Australia on the climate system, knowing that we are some of the heaviest emitters in the world and we live exceptionally wealthy lives, most of us here in Australia, comparative to the rest of the world. So, I knew that, you know, kind of the individual impact of our lives is quite significant and more than that I knew that the climate system was changing with this great rapidity. And I saw that in my academic work. And I remember working at that time on a paper that was looking at when current extreme climate events would be average. So, if we think about the worst heatwaves that you’ve lived through, when will that be average? And for some of the locations that we’re looking at back in 2017, it was going to be in our models projected for around 2030, 2040. And I was thinking, oh my God, this baby is going to be in high school [or] uni. That’s not the future. So, it was this huge kind of uncomfortable tension around desperately wanting a child and feeling like that was a good thing to do. But also, what world would this child grow up in? Would this child want children or feel that that was a possibility? And I don’t know that I’ve ever really resolved any of that. So, a message for others I don’t have. You know, I deeply believe people should have the number of children that they want. And I think it’s really unfortunate when people have more or fewer children than they really want. So, I certainly don’t think people should have necessarily hesitations, but I think it is a really big consideration for a lot of people knowing that and having experienced the impacts of climate change and thinking, well, what will their world be like in 2050, 2100? And that was a really difficult thing for me. And it still is.

Knowing everything that you know, collecting all of the data that you do and pulling together all the reports that you do, what gives you hope?

Well, I think they do, which is, you know, it’s a lot to put on children. But, you know, at the same time as worrying about their future, babies are just this immense gift to the community who love them. And they are full of joy and they’re deeply immersive. And I think to me, I get a lot of kind of inspiration and passion for my work from them and my commitment to them. But also, I think I must be a fairly optimistic, positive person. You know, I do really worry about their future, and I did spend a lot of that Black Summer looking at real estate elsewhere where I was just going to leave. I just can’t handle this anymore. But at the same time, I do think there is so much potential for us to halt that trajectory that we’re on to a future I don’t want my children to live in. And, you know, you see that through all these climate conversations. Is that deep hope that things can be better, and we can achieve that.

So thinking about Canberra, what is it about Canberra’s ecology that makes it unique and an interesting place to be studying these impacts and collecting this data?

Yeah, so Canberra is I mean it’s just a beautiful place. So, most of the ACT is actually comprised of National Park, so around 80 per cent of the city’s land is Namadgi National Park, which is just a spectacularly beautiful location. But we also know that it’s quite vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. We had bushfires in 2003 that affected the park, and it wasn’t able to recover between 2003 and the Black Summer bushfires. So, in January 2020 we had a huge catastrophic fire that occurred in the Orroral Valley and ended up burning a large fraction of that park. And it’s really unclear how the park is going to recover because these high alpine bogs and fens, the high places in the mountains aren’t used to having fires that are occurring that frequently. So, in terms of the natural environment, it is quite vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. It’s also quite far from the sea. So, we don’t have any of those moderating effects of being close to the ocean, which really help with those extreme temperatures. So, a small change in global average temperatures. You know what we’re talking about in terms of limiting warming to one and a half or two degrees is likely to have a big impact in terms of the extremes of temperatures we see in summer in Canberra. And we’ve already seen that that it used to be quite uncommon in Canberra to have days above 40 degrees. There was a 25-year period from the 1970s, in the 1990s where there were no days, they exceeded 40 degrees.

Oh wow.

Yes. And since I think 2009 we’ve had over 16. So, we’re having this huge increase, you know, 44-degree days. So, we’re quite vulnerable to extreme temperatures and we have potential issues with water security. So, it is a place that is immensely beautiful, but also has that kind of fragility around impacts of climate change.

Ideal world. All of your recommendations are implemented. What does the ACT look like in the future?

See, this I think is really exciting to think about rather than just the, you know, we’re heading to this catastrophic climate change is actually what is the potential for positive change. And I think for the ACT there is so much. So, we’ve talked a lot about climate mitigation, so reducing greenhouse gas emissions. But I think there’s also great potential there for climate adaptation and having a really climate resilient city. And during the Black Summer bushfires that I’ve talked about at such length, we realised that we’re not particularly resilient. There’s a lot of homes that aren’t heat resilient. None of us had much smoke resilience. So, I think there’s a huge opportunity to look at our urban environment and build in that climate adaptation. So, we have a really climate ready city. But the other thing I think we need to look at is around our overall ecological footprint. So, in the ACT our ecological footprint is nine times the size of the ACT. And what that means is that if every person across the globe lived like a Canberran, so lived like me, we’d need nine planet Earths.

We would really like [Western environmental reporting] to sit alongside cultural indicators that are provided and determined by Ngunnawal people, that we have both of those sitting within a State of the Environment report.

– Sophie Lewis

That’s not reasonable.

No, we don’t have those. That’s eight too many.

So what is it about the lifestyle in the city that creates that?

So we’re typically, you know, compared to the rest of Australia, reasonably wealthy in terms of household income. And I think that really drives a kind of a lot of consumerism or a lot of consumption, I should say. And that’s what we saw with the scope three emissions, it comes back to that. So much of our carbon footprint is because of goods and services we bring into Canberra, and that’s the same for our ecological footprint. We have report after report showing that Canberrans have really large house sizes compared to other cities and we tend to kind of consume more. So, looking at our ecological footprint shows that that’s not tenable, that is not a sustainable way to be treating our environment. And I think if we’re looking to 2030 or beyond, we have a great opportunity to look at that and say, well, what aspects of that do we not really need? What can we give up without kind of giving up having reasonable comfort. But, you know, the nine is really quite shocking to me that that isn’t reasonable. That’s the first reaction, is that that’s not going to work. So, I think –

It doesn’t work.

Looking at both of those we have great opportunity to have a climate resilient city that is healthy for people. Places that really work for people is what’s on offer there.

Thank you so much for your time, Sophie. It’s been absolutely fantastic chatting with you. Please join me in thanking Sophie. To follow the program online you can subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. And visit the 100 Climate Conversations exhibition or join us for a live recording, go to 100climateconversations.com.

This is a significant new project for the museum and the records of these conversations will form a new climate change archive preserved for future generations in the Powerhouse collection of over 500,000 objects that tell the stories of our time. It is particularly important to First Nations peoples to preserve conversations like this, building on the oral histories and traditions of passing down our knowledges, sciences and innovations which we know allowed our Countries to thrive for tens of thousands of years.