Norman Frank Jupurrurla is a Warumungu Traditional Owner who lives with his family at Village Camp, near Tennant Creek in the Northern Territory. This beautiful region, where the average summer temperature is 37 ̊ celsius, is on the front lines of climate change with its people increasingly at risk of heat-related health problems and deaths. He is campaigning to bring solar power to his community. Like many remote communities across the NT, the residents of Village Camp currently pay high prices for expensive diesel power or polluting gas power that they do not want. He is a board member of both the Julalikari Council Aboriginal Corporation and Anyinginyi Health Aboriginal Corporation, dedicated to cultural and community development work that helps his people live healthy lives.

Rae Johnston is a multi-award-winning STEM journalist, Wiradjuri woman, mother and broadcaster. The first Science & Technology Editor for NITV at SBS, she was previously the first female editor of Gizmodo Australia, and the first Indigenous editor of Junkee. She is a part of the prestigious ‘brains trust’ the Leonardos group for The Science Gallery Melbourne, a mentor with The Working Lunch program supporting entry-level women in STEM and an ambassador for both St Vincent De Paul and the Australian STEM Video Game Challenge.

Warumungu Traditional Owner and Elder, Norman Frank Jupurrurla, is fighting for his climate change-affected community to get access to safe housing and affordable, non-polluting solar energy. As remote communities experience dangerously high temperatures, better housing standards protect health, energy security and community.

Summer is too hot now. So, you know now we gotta work around that climate as well. It’s climate changing everything now these days, even our ceremony and the way we live now.

– Norman Frank Jupurrurla

We’ve got to change our ceremony date days and months because of that climate… because you can’t have young fellas sitting out in the bush or old people singing out in that 49°C heat. It’s no good. You know, it can kill.

– Norman Frank Jupurrurla

I’m the very first Wumpurrarni person to have solar panels on my roof, and not only in Tennant Creek, in the Northern Territory.

– Norman Frank Jupurrurla

I’m trying to build three houses on my block the way, how we want to build it in our own design so that we can build something that we suit and it can fit into our climate, in our Country.

– Norman Frank Jupurrurla

Wumpurrarni way, Papulanyi way — that’s how me and Simon worked. He work with me, with Papulanyi way, he teach me things, Papulanyi way. And me, I teach him my way, Wumpurrarni way.

– Norman Frank Jupurrurla

These people in the city, they never come out and see how we lived for the last hundred years.

– Norman Frank Jupurrurla

Summer is too hot now. So, you know now we gotta work around that climate as well. It’s climate changing everything now these days, even our ceremony and the way we live now.

– Norman Frank Jupurrurla

Welcome, everyone, to 100 Climate Conversations. Thank you so much for joining us. Yiradhumarang mudyi, Rae Johnston youwin nahdee, Wiradjuri yinhaa baladoo. Hello, friends. My name is Rae Johnston. I’m a Wiradjuri woman, but I was born and raised on Dharug and Gundungurra Country, which you might know better as the Blue Mountains region. That’s where I have responsibilities to community and Country and I’m very grateful to be living there today. And I’m also very grateful to be here with you on the Unceded land of the sovereign Gadigal and I wish to pay my deepest respects to their Elders, past and present, for the great sacrifices that they have made so that we can be here today. And as we start this conversation, it’s important to remember and acknowledge and respect the fact that the world’s first scientists and technologists and engineers are the sovereign First Nations peoples of this continent, from the world’s oldest continuing cultures. And in my everyday I’m a STEM journalist and broadcaster, and I get to speak to some absolutely incredible people that are working in their particular fields, from their perspectives and from their lived experiences to combat the greatest challenge that we are facing as human beings, and that is climate change. Today is actually number 76 of 100 conversations that are happening every Friday. And this series represents 100 visionary Australians that are taking positive action to respond to the most critical issue of our time, which is climate change. Now we are recording live today in the Boiler Hall of the Powerhouse Museum, and before this was home to the museum, it was the Ultimo Power Station that was built in 1899 and supplied coal-powered electricity to Sydney’s tram system and that ran all the way up into the 1960s. So, in the context of this architectural artefact, we shift our focus forward to the innovations of the net zero revolution. Now Norman Jupurrurla Frank is a Warumungu, traditional owner, and he’s dedicated to cultural and community development work that helps his people live healthy lives. He lives with his family at Village Camp near Tennant Creek in the Northern Territory and is campaigning to bring solar power to his community. And Norman is also the board member of the Julalikari [Council Aboriginal Corporation] and the Anyinginyi Health Aboriginal Corporation as well and we’re so thrilled to have him join us today. Please join me in welcoming Norman. Thanks, Norman. I’ll start by asking you to tell me about your Country. Tell me about yourself.

Yeah. My name is Norman Frank Jupurrurla, and I’m from Tennant Creek. I’m a local Warumungu man and I am a Traditional Owner, Native Title holder for Tennant Creek and surrounding for the Warumungu people. And I’m an Elder as well. And I wear a few hats around Tennant Creek in the township like Julalikari, Anyinginyi, Nyinkka, CLC, a few places there. I grew up in Tennant Creek, I’m a local young fella from there. I went to school there, but only went up to grade five or six because I was coming in from the station ’til we moved from the station back in 1977, back into the township when people had their rights to move into town. That’s when my people moved back into Tennant Creek then. I’d like to say a few things about myself, who I am. I’m a Warumungu boy. I’m from a clan group north of Tennant Creek, from a place called Phillip Creek. From there, we call ourselves, our clan group call ourselves, Bourrorrdoo people we are– I’m a Bourrorrdoo man. Well, I’m from the Bourrorrdoo clan group. We are from the Jalajirrpa mob, Jalajirrpa clan group. That’s the White Cockatoo we call– where my clan group come from. From the place Bourrorrdoo Country. Yeah, and that’s who I am. And that’s my totem from my grandfather’s side, from my father’s father’s side. And we use that for ceremonies through our initiation time. We use our white cockatoo, a few other totems that come across through our Country so that we fit in, that we, when we have our ceremony, fits in our young fellas and our shields, and our painting on the ground or our totem to go with the ceremonies. When I went through, I went through my ceremony in another place, on Alyawarre Country at Murray Downs, but my father used my totem from my Country to sing me with my Country’s totem so that I can fit into my great grandfather’s name. So, I carry my great grandfather’s name– my grandfather, so, my father’s father’s name. His name was _______. That’s my grandfather’s name — my father’s father’s name. And I’ll carry that today because after the ceremony with my grandfather’s totem and his name. And that’s why I carry his name still today. But I never really went to school, really, much. Because I don’t know, you know, how to read and write, really. But I’m up here, you know, in that 100 [Climate] Conversations today. And I like to, you know, tell my story what I do today. I try really hard for my people through climate and, you know, trying to tell people climate change, because that’s a really big thing now. But when I was a kid and when I was growing up in the bush, I never heard of climate change. I never heard of it, never did. And now I see it today, you know, on news and on TV or hear on the wireless people talk about climate change now today. And it’s true. It’s happening out there, ‘cause our Country is changing now and all these things are happening. Billabongs gone dry, our permanent water holes and rock holes. You know, I’d never seen it when I was a kid, never went dry. But now today, sometimes today there’s no water in there again. And the life– bird life, the plants, the bush tucker’s all not coming out in the right season. It’s coming out in the wrong season. Animal breeding’s different now, in the wrong season — coming out of the hole or burying himself up, you don’t see him anymore because– and sometimes they come back out at the wrong time. So, like lizards [are] dead. You don’t see him in winter, but wintertime you still see him coming out. Turkeys, you know, with eggs and chickens in the wrong time. Even emu. The only time emu have chickens is wintertime, now you see emu having chickens and it’s summer. But, you know, I don’t know. We don’t see that. But now there’s climate changing. It’s real. It’s out there, you know. So, we’ve got to start thinking what we’re going to do.

And it gets really hot out there, too, doesn’t it? So it’s like 49.9°C in Tennant Creek. What’s it like out there on hot days like that?

Oh, terrible. You can’t go out. You can’t walk — the sole on your boot melts out. Walking along bitumen, you feel these rocks stick in through your boots. Then you look down and your sole’s gone.

Got no boots.

No boots. True. It happens a few times. And you know, it get that hot it burns, trees– kill all these trees, nice shade some of them, you know, the African mahogany trees used to be at the at the dam, the Lake Mary Ann Dam — there’s nothing now, because the heat too much. Too much just burned. As you say, it was 49°C. I was sitting there once watching that clock, was it going to tick over to 50°C? It’s just sitting on 49°C.

How do you keep yourself cool?

The only way you can keep yourself cool, have the sprinkler on or sit outside. If you’re going to be outside, have a swimming pool or something, at least. Or you got to be inside the house. We don’t have split system or aircon. But if you’re in the bush, you’ve got to sit near the waterhole or you’ve got to be swimming. If not, you’ll be burnt. Totally true. That’s how hot it gets.

So how does that hot weather change the way that you live? You know, it would have been different when it wasn’t quite that hot, right?

Nah, it was different. I remember in the communities back in the early 80s and early 90s, we used to live in these old tin sheds out in the community. That was then, you know, and it wasn’t that hot. We could stay in them tin shed. But now, I think you never can now, because this climate is getting hotter and hotter. It’s changing nearly every decade. It’s you know, it’s more hotter. Now, you can’t live in a tin shed anymore. Not like we used to in the station. We used to live in tin sheds. Yeah, back then and nothing now.

How does the changing climate make you feel seeing those changes to your Country?

Well, it hurts me, it really hurts me ’cause we can’t blame ourselves. We gotta blame the climate, how it’s changing today. But like I said, old people didn’t know anything about climate and it was coming. Now, you know, it doesn’t fit. In our time today we live in because our ceremonies, it’s different as well. We’ve got to change our ceremony date days and month because of that climate. We need to have a ceremony early now when it’s probably just coming into winter or starting of winter, because you can’t have young fellas sitting out in the bush or old people singing out in that 49°C heat. It’s no good. You know, it can kill. Young fellas today, we have to, you know, sing them in a different time now and then we’ve got to work with school as well, ’cause school holidays or at Christmas break, that’s when we usually do. But that’s summer, it’s too hot now. So, you know, now we’ve got to start– we’ve got to change. We’ve got to work around that climate as well. It’s climate change. Everything now these days, even our ceremony and the way we live now.

We’ve got to change our ceremony date days and months because of that climate… because you can’t have young fellas sitting out in the bush or old people singing out in that 49°C heat. It’s no good. You know, it can kill.

– Norman Frank Jupurrurla

Now, in our last Conversation, we talked to Dr Simon Quilty, who you have a longstanding friendship with and you collaborate with. He’s a medical doctor that’s been working in remote communities for over 20 years. What’s it been like working with Simon?

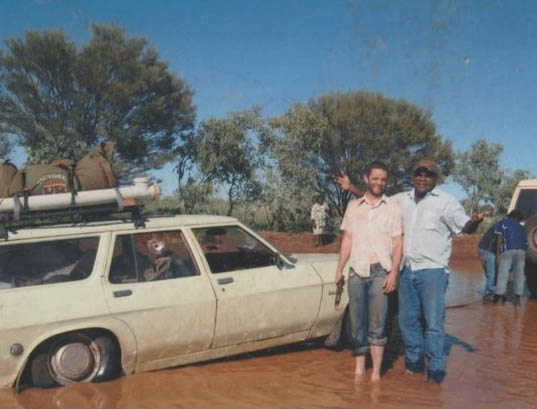

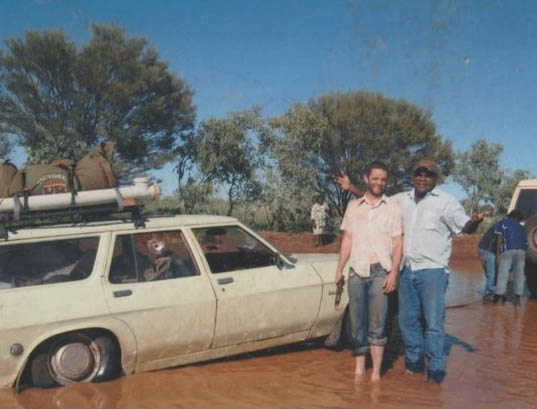

Really good. Oh well, he was my best mate. Me and him met years ago. When I first met him he was a young fella from Sydney. And I’m a man from the bush. And he came out, worked in a remote community called Utopia — this was more than nearly 27, 26 years ago. That’s when I first met him. And he’s a very smart man, very smart man, Mr Simon Quilty. And Simon Quilty, he taught me a lot, in his way, you know, in the European way, Papulanyi way of living. And I teach him a lot about Wumpurrarni way, our way, and when you work together. I’m with him now today, still working with him, and get along with him. And he’s like my brother. I gave him a skin name. That’s me, Mr. Jupurrurla, as well. So when he go out in the community, say my name is Simon, my skin name, Jupurrurla and he fits right in with everybody else, see? Because he got a skin name from me and he’s my brother, too. So, and Simon, me and him work now today, really good. And we doing things, you know, and work around climate. And when I went around to see him in Alice, he was staying in this house at Alice Springs and he showed me he doesn’t have to pay power much anymore because it gets that solar on top of his roof, he’s got panels. And I said, ‘Hey, mate, how you got that there?’ And he said, ‘They were here when we moved into this house it was already there’ and I reckon, ‘Well I’d like to have one of them one day’ and he said, ‘No worries, we’ll try to get you one.’ And then he helped me to get one put on my roof. And right now, today, in Tennant Creek I’m the very first Wumpurrarni person to have solar panels on my roof, and, not only in Tennant Creek, in the Northern Territory. So, it was a very smart move from my brother Simon Quilty. That was a very smart thing. And now, you know, I’ll get interviewed from nearly everybody or from, from medias, from everywhere, all over the world — come and ask me about my solar. And now I want to see solar, right through the Barkly. And now, with this solar mob, a lady called Lauren, she helped me and she’s helping a few other communities. Most from Tennant Creek just passed about 20 km out of Elliott, a place called Marlinja, where my family come from as well. Helping them and got them started with solar on their roofs that as well. And, people from Borroloola, she’s helping them about there in their community too as well. So, she does a really good thing and doing a really good job for everybody, you know. And, I like to see that right through the Barkly. I want to see the government to try to help every Wumpurrarni as Lauren helped me and Simon did putting up panels. But, it’s a challenge with the government. But you’ve got to go through a lot of hoops to get there. And I did. I had to go through, a lot of hoops, not only with the housing. I had to go through with power and water as well. And I’ve got a panel up there and I put that up there on my roof. But then, then you had to wait another three months with power and water to just put one switch on.

Three months?

Three months.

To put a switch on?

Yeah, to flip one little switch. Just on and off switch. Yeah, took them three months.

Tennant Creek. It has over 300 days a year of sunshine. That’s a lot of sunshine.

Oh yeah.

So, it’s pretty important for the community to be able to have solar out there, isn’t it?

Yep. Especially out in the communities. You know, you can’t be using diesel, burning diesel all the time, because it costs too much. Service, oil, all that, it costs too much. But solar, nobody’s going to take solar away, or the sun away from you. The sun’s going to be there all the time. So, why use diesel and generators while you got that sun there? So it’s a very smart thing today. I reckon we should have more solar in these communities or around in the township as well in these houses. Because it costs too much.

And you need to have the solarto be able to power things like air conditioning there because, tell me what it’s like to live in the houses at Tennant Creek. What are they built like?

Well, I reckon that’s true. You need power and you need solar. Because, if you’re like me, because I’m a sick man, I’m not a really healthy man, I got chronic disease. I’ve got a lot of things wrong with me. I got renal, you know, I got sugar and all that. And you need a fridge. You need a fridge to go on 24/7 because of that heat. And if you’re in summertime, you need a fridge. You have to need a fridge. That’s one thing about health today. You need a fridge for your medication, because the doctors and the nurses in these hospitals or the health clinics, they don’t know how we live. They don’t know. They’ll send you back home with all this medication. They don’t know where you’re going to stick it or what you do at home. Because that’s one thing about, you know, the way the Wumpurrarni people live. Some of us people we live at bush. Some of us just live in a windbreak just in the outskirt of town, some live in a house. But the main important thing, we need a fridge in the house for us today. We need power all the time. Power. That’s the main number one key today to keep our fridge going for our medication. Keep things cool, because you can’t keep your insulin in a bag. If you’re on insulin for your sugar the nurses always say you got to keep this in a cool spot and put it in the fridge. You put it outside one day, it’s like an egg. It’ll boil, it’ll cook and then you can’t take it. You can’t shoot yourself up the next day because it’s off already.

And how is the power in these houses at the moment without solar? How do you get power?

Well, at the moment, we live off the power, of the whole township, from the power house and we use them smart metres today, and smart metres, how they work you have to put money in — my daughter was telling me she put $20 in nearly every day just to keep that power going, $20 every day. You put $20 in now, by the time tomorrow morning, you get up it goes off at nine o’clock. Then you’ve got to put another $20 or $30 in. And if you use your power over the weekend, you get up Monday morning — if it went off on Friday afternoon, it doesn’t go off ’til Monday morning until nine o’clock again. And then you’ve got to back pay the power. Sometime it clocks up to $70, $80 and then you’ve got to pay all that again back before your power come back on. You know, and it costs too much. Too much.

But you have to have it going.

You have to have it going, that’s right.

You can’t live.

You can’t live. Because you’ve got kids. You’ve got kids and you’ve got old people staying in the house. You need a place. You need to be cool, cool in summer. And then when you get to winter, you need to keep it warm. You need to use that heater then. And then if you’ve got no power, what are you going to do? Can’t do nothing. You have to make a fire or something, sit outside.

So, there’ve been some newly built government houses in your community, and I’ve seen photos of them. They don’t really look like homes to me. They’re just like buildings, aren’t they?

I’m the very first Wumpurrarni person to have solar panels on my roof, and not only in Tennant Creek, in the Northern Territory.

– Norman Frank Jupurrurla

I reckon, they build these houses today. They’re not fit for the community and they’re not suited for the climate for us today. I think the whole house I’m living in, it’s about 48-year-old, or somewhere there, 45-year-old house, had been built back in 1980s or 1980, I think that year. And that house I’m staying in I think it had been built for England because, that house I’m staying in, it’s very, very hot in summer but when it comes to winter it’s very, very cold.

They don’t use any insulation, do they?

I want to see in my windows. But you know, my kids can’t even look through it — it’s too high.

So, what’s wrong with the new houses? Tell me why they don’t work.

They build it the same and they’re like prison. If the doors can’t open and if you’ve got a fire in the house, I wouldn’t know how you’re going to get out of there. ‘Cause I tell you what you’ve got them bars, you’ve got them screens at the window, you can’t break through them and they’re all perspex, the glasses. But they’re not glass.

Perspex, not glass?

Yeah. You won’t break it, you won’t get through it.

So, you and Simon, you have a new initiative that you’re getting off the ground, a new housing collaboration that you’re working on.

Yeah.

I’m trying to build three houses on my block the way, how we want to build it in our own design so that we can build something that we suit and it can fit into our climate, in our Country.

– Norman Frank Jupurrurla

So, tell me about it.

We’re working on a collaboration with– we’re trying to start a little corporation sort of thing, building thing, called Wilya Janta. What we’ve– well, that’s what call it, Wilya Janta but we try to call it Wilya Arrtjul Janta really, that means standing– ‘we are all standing strong’. But Wilya Janta mean, in my language, ‘standing strong’. And we really want to call it, me and Simon will say, Wilya Arrtjul Janta because that’s about all of us. Everybody. So, we’re going to try, but I’m trying to build three houses on my block the way, how we want to build it in our own design so that we can build something that we suit and it can fit into our climate, in our Country. And now, you know, where we live, how we live so that the house fits how we fit into the house. And culturally, I want to do really culturally, that we can have two kitchens, fireplace outside because really, you need a fire all the time. Wumpurrarni people we live ’round a fire that’s to keep the spirit away. Because if you don’t have a fire and smoke to keep that jangalkki — jangalkki means spirit — you’ve got to keep that spirit away. Yeah, because that’s a very important thing, because if you’re gonna have baby around and kids, the jangalkki target babies all the time, or kid — will get into him. Lippi — dig it in there. His little, his nails, his fingernails, a claw. Very, very spiritually. That jangalkki, it’ll bite him, gets in the kid. That’s why you need a fire all the time. That’s why I said to Simon, ‘For a start, you’ve got to build a house. I have to have a fire pit. And if I’ve got to have a house, I need two kitchens’. And he asked me why. I said, ‘That’s culturally, ‘cause we need two toilet, two– got to have one outside, another one in, because you can’t be walking on top of each other’, I said, and always Wumpurrarni we will– we’ve got poisons, you know, against out mother-in-laws, father-in-laws, daughter-in-laws or son-in-laws, we can’t be walking on top of each other or bumping into each other. It’s culturally, we can’t be doing that. ‘Cause we will call ’em miyimi, we’ll call ’em lampara, we’ll call ’em ________ — son-in-law, daughter-in-law that’s how we’ve got to live. One time before I remember in the station, back in the bush, we used to have single quarters — men’s, women’s, we call them Milkarnaja, that’s woman’s quarters, Jungkayi that’s men’s quarters. And in a Jungkayi and a Milkarnaja there has always been an old person, always been there. Yeah, all the time staying there. And when the young people get pushed out of the camp from their mother and father, when they’re teenagers, 11, 12, 13-year-old they go to the single quarters and they’ll go stay there and, you know, there will always be someone there and they grow up there and that’s where they, you know, find their way then in their quarters. And we always sleep with our heads to the east and our foot to the west. That’s the way we, everybody, all grow up even in the bush. And that’s how we need to sleep. If we sleep the wrong way, we wake up your mind somewhere. You’re different. You don’t know which way north, east or west is — you’re warunga, warunga mean ‘mad’. In your purluju. It’s in your head. Your bearings are wrong.

So, if you’re you’re sleeping in these government-built houses, they’re not built facing the right way, so you’ve got all your beds like this.

Sleeping the wrong way, that’s right. They put us through that way. The same thing today. The government, these houses, we just get chucked in there. We got no choice. No choice, nothing. Soon as your name come up, you got a house. All they do is give you a key. And they chuck you straight in these houses. In these houses without induction, nothing. You don’t learn nothing. You don’t know anything. They don’t give you a fridge, they don’t give you anything. You’re going to be in that house, you’ve got to make, find your own way. All they give you is they hand you over the key and the house and, you know, that’s just not right. And Wumpurrarni people, you know, they’re just happy they have a roof over their head again and a house and then they don’t tell them anything until– they learn along and pick up theirself. And that’s very true. And these houses, they chuck us in, we don’t even work with them. That’s their design, their building that’s it. That’s how they’ve been doing that for years. I’ve been doing that for years. Since mission days when they used to have our kids, our great grandmothers and grandfathers in the mission, they used to take them in these missions to these dormitories, chuck them straight in there. Trying to teach them, go to school, learn them how to speak English. Don’t want to hear them talking their language or singing in their own– they change their ways. Still today. They still brainwashing our people with all this. People trying to go back to community. They’re sucking them back into town or in these bigger communities. And building their way. And how they want them still there. Everyone, the same thing. They’re not changing this government. I see this happening still today in these bigger communities like Ampilatwatja, like at Utopia. Utopia is a big community. It’s a very big community. These people have been moved back in their homeland, back to these bores. They’re not building them places up anymore, these communities. They’re building one place up in the middle of Alpara, Alpara, they’re sucking them back into one little group again because they got their thumb over them, try to get them people. Even Ampilatwatja, same thing, you know. And I feel sorry for these people. Why are they listening to these government? Can’t they break away and try to do things themselves, you know? And now I like to see Wumpurrarni people go back to our old people, go back to what they were thinking. Go back to the timeline, what they put these places for, for a purpose. Our organisations they’re put there for a purpose in our community. So Wumpurrarni people, we’ve got to think. We’ve got to go back to this timeline. My old people, they couldn’t read or write, but they fought for my Country. They fought for my Country and they’ve put these organisations there like Julalikari, like Anyinginyi, Papulu Apparr-Kari Language Centre — they put them there for a purpose. So, nobody gonna to change things but what old people put there — they put them there for a reason. For the next generation, the next generation, next generation and the next generation. Better think what’s the purpose the place been there for? And you know, it’s there for a reason and nobody’s going to change it. If somebody’s gonna change it, they jump right back. And I always say, why old people put it there for? They put it there for a purpose. See, like Julalikari it’s there for housing and for work, for training for our people. That’s what the purpose had been there for, so nobody got to change that way. Anyinginyi, they put that place there, that health centre for our health and our people. Instead of going to the hospital, you didn’t have to book, you didn’t have to make appointments. You’re supposed to just walk straight in and say, ‘Look, I need to do my dressing today’. It’s not for appointments. Nah, it’s just there for our community. And my old people, they put them things there, but they couldn’t read or write, but they had a vision. Vision. They didn’t have a plan but had a vision. No plan. That vision then drive them to where we are today. That’s why I like to see my people always. We always have to go back to that timeline. That’s what I think today, and a really good thing, my old people never heard of climate change, but now we have to think about that today. It’s a really big thing.

You’ve been co-authoring some papers, some academic papers with Simon. What’s that process been like?

Well, that process has been really good because we need to get that message out there to Papulanyis, and people around the world need to hear how can we work in two ways on this world today? Wumpurrarni way, Papulanyi way — that’s how me and Simon worked. He work with me, with Papulanyi way, he teach me things, Papulanyi way. And me, I teach him my way, Wumpurrarni way — what my thinking and how we feel. Because what we feel when I tell him, warunga it’s your purluju. Your kumpumpu, your brains. You need to think. You’ve got to use your brain. Before you’ve got to do things you’ve got to have feeling. You’re munkku, I always telling him how you’re feel. Your munkku always trying to tell you something. What’s right? What’s wrong? That’s how I always tell him all the time. You’ve got to have your gut feeling mate. That’s what I always say to him and he always say, ‘Oh, that’s true’. You know, Wumpurrarni and Papulanyi, we think the same thing, but Wumpurrarni’s a bit smarter. And we Mukunjunku. Mukunjunku’s with everything ’cause everything that we do we think before we do something. We’ve got a plan. That’s why I always say, all the time, ‘The important thing you got to do, my mate, you gotta shake that bush. If you want to make something happen, you’ve got to shake that bush all the time. You’ve got to talk. And you’ve got to be strong. You have to shake that bush. If you just shake that bush, you’ll have seeds falling off the tree, mate. And once hit that earth, it comes up again. It grows like me — I come from the grassroots. That’s what happened to my older people. They put something there, but they fell over. But what they did, they made sure to put us young fellas, young people behind coming up again. That’s why we come from the grassroot, grassroot people. And as we come up behind now, old people, we’ve got to be stronger. We’ve got to work that trade with this world we living in today with technology and we’re getting smarter. And my kids, I want to put them to school learning more, because the more they go to school more they learn more and get smarter, more than us. More than me. More than my old people. ‘Cause, I didn’t go to school, like I said, you know, and my great grandfather and my grandfather didn’t go to school, but they were smart. ‘Cause they planned something that they had a vision of what they wanted to see. And I like to see my kids, what they’re going to come out to be. My great grandkids, grandkids going to be, what they’re going to be. I like to see. I see my kids now, but I want to see my grandkids, how they’re going to come in next 10 years, five years’ time. They’re going to be smart or they’re going to be like me. I hope one day, because my father was a very smart man — he done a lot of things for me. And when he was sitting on his last leg and ready to go, he said to me, he said to us all, all of us, my brothers and sisters and his grandkids. ‘Well, I left this place on a platter for yous’. That’s why today we can go out there today we got a home to go to, we’ve got a homeland. My dad left that there for me, a legacy, something behind. And when I go, I hope something is going to be left behind for my kids. Like Wilya Janta now, you know, I want to put that in a place — leave that behind for my great-grandkids and my kids.

How do you think Western science and Indigenous knowledge need to work together for the future?

That’s why we talk about two-ways learning. That’s two-ways learning. You gotta learn two ways. Wumpurrarni way, Papulanyi way. That’s how we think. The more you learn Papulanyi way. The more smarter you get. Like I always tell Simon, I tell him. ‘You see Wumpurrarni man? A blackfella, if he’s smart in two ways, you be careful. He’s a very dangerous man. Very powerful’. I always tell him that. And he’ll always say, ‘You’re right there because he’s a very powerful man.’ He think two ways, then. And that’s the way I think as well.

Do you think that we can solve the problems that communities like yours are facing with housing, in the future?

See these houses, what me and Simon are doing, these three houses we want to try to get going for Wilya Janta and for the community in Tennant Creek. These three houses, they’re not the same. The one that my missus worked with the architect and her design, it’s different than my sister’s and my sister-in-law’s. ‘Cause we’re trying to do three houses on my block and the three houses we want to use for a display for the time being. Display, so that people can come and see, you know? And we’ll get that message out there through council meetings so that they can, someone, people can come and see what kind of a design and have your own choice. How you want to design your house.

Do you think the people in the cities know what it’s like, the housing out there?

Wumpurrarni way, Papulanyi way — that’s how me and Simon worked. He work with me, with Papulanyi way, he teach me things, Papulanyi way. And me, I teach him my way, Wumpurrarni way.

– Norman Frank Jupurrurla

I don’t think so. I don’t think so. These people in the city, they never come out and see how we lived for the last hundred years. You know, like now we try to move along and change. We’re going to live in this time today. With the roof over our head. Not like one time, we used to live in humpies, you know, without a door and a window we could walk straight in and out. Today, we’ve got to walk in the door and look through a window. So we’ve got to have a house.

Through the perspex.

Yeah. So, we’ve got to try to move forward.

What’s your message for the people in the cities, the people that don’t have any idea what it’s like to be out in the community? What do you want them to know?

I like to let them know we battlers, we struggle. We’re trying to move forward Wumpurrarnipeople, we wanna live like you, in the city today. We want to live in a house, a decent house, building, something that we can stay in, somewhere we can keep warm and cool in summer and, you know, have a roof over our head from rain. We don’t wanna be back in no old humpy up here again now want to live like you today in the city with a roof over our head. Walkin’ through a door. Switch on a switch for a light at night. That’s the way I want to see that message for these people living in the city. Have a look how we live. We’ve been living for a long time, you know, in the bush without a power. But can we move forward today to help Wumpurrarni people? You know, have a look back. Look back how we used to live. Can we live in the same world today as we’re all working in this Country today and how we living? We should be together. These city people– I look at this place, they live with time, date, time, date.

Calendars.

Days, calendars. You know, and like me, I come into Sydney. I see this place, too big for me, too rushy, too big. And I said to Simon, ‘If I take a walk up the street, I’ll get lost. I’ll get lost. I wouldn’t know which direction’.

You can’t see where you are.

I can’t see. If I walk out in the bush, I know where I am. I can get my bearing right. I can go down a hill, come up paths. I’ll know where the creek is. But here everything looks the same. You have cars, you got a bitumen road, without a sidewalk, you know. I’ll get lost. That’s what I said to Simon. Another thing is, I can’t read or write. Every sign will look the same to me.

So what needs to happen now to get the housing corporation happening? To make that a reality and help everyone design their own home for how they live?

Well, we need to collaborate. We need to work together. Support us, or something. We’re looking for a bit of support, that’s all. Just asking for support. That’s what we need. Me and Simon and that’s what we would need to do. We need to get that support to get us going. And then we might work together and, you know, work together and get something up and go, because that’s what I like to see. And then I hope, we would, ’cause I like to see my people, and me at least, you know, out there and trying to do something for my people and not only for mbyself, for the whole Barkly. And in the Barkly there’s not any one tribe, there’s about six or seven different tribes and I like to see, you know, help the lot, not only my tribe I wanna see Warlpiri, Warlmanpa, Wakaya, Alyawarra, Warlpiri people, Jingili, Mudburra you know, we all lot together, to help each other and, you know, get a better housing and our own way of designing our own houses. That’s the way I like to see.

Thank you so much for your time today, Norman. It’s been fantastic talking to you.

Thank you.

These people in the city, they never come out and see how we lived for the last hundred years.

– Norman Frank Jupurrurla

Now to follow the program online you can subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. And visit the 100 Climate Conversations exhibition or join us for a live recording, go to 100climateconversations.com.

This is a significant new project for the museum and the records of these conversations will form a new climate change archive preserved for future generations in the Powerhouse collection of over 500,000 objects that tell the stories of our time. It is particularly important to First Nations peoples to preserve conversations like this, building on the oral histories and traditions of passing down our knowledges, sciences and innovations which we know allowed our Countries to thrive for tens of thousands of years.